You probably have a favorite song you didn’t love the first time you heard it.

But you listened to it so many times that it quickly became familiar.

And now you love it.

Or a brand of cereal you keep buying, not because it’s the best, but because it’s the one you know, or the one that was in your house when you were younger.

Why do we keep reaching for the familiar, even when something new might be better?

It’s not just habit.

It’s science.

Why familiarity feels good: the mere exposure effect

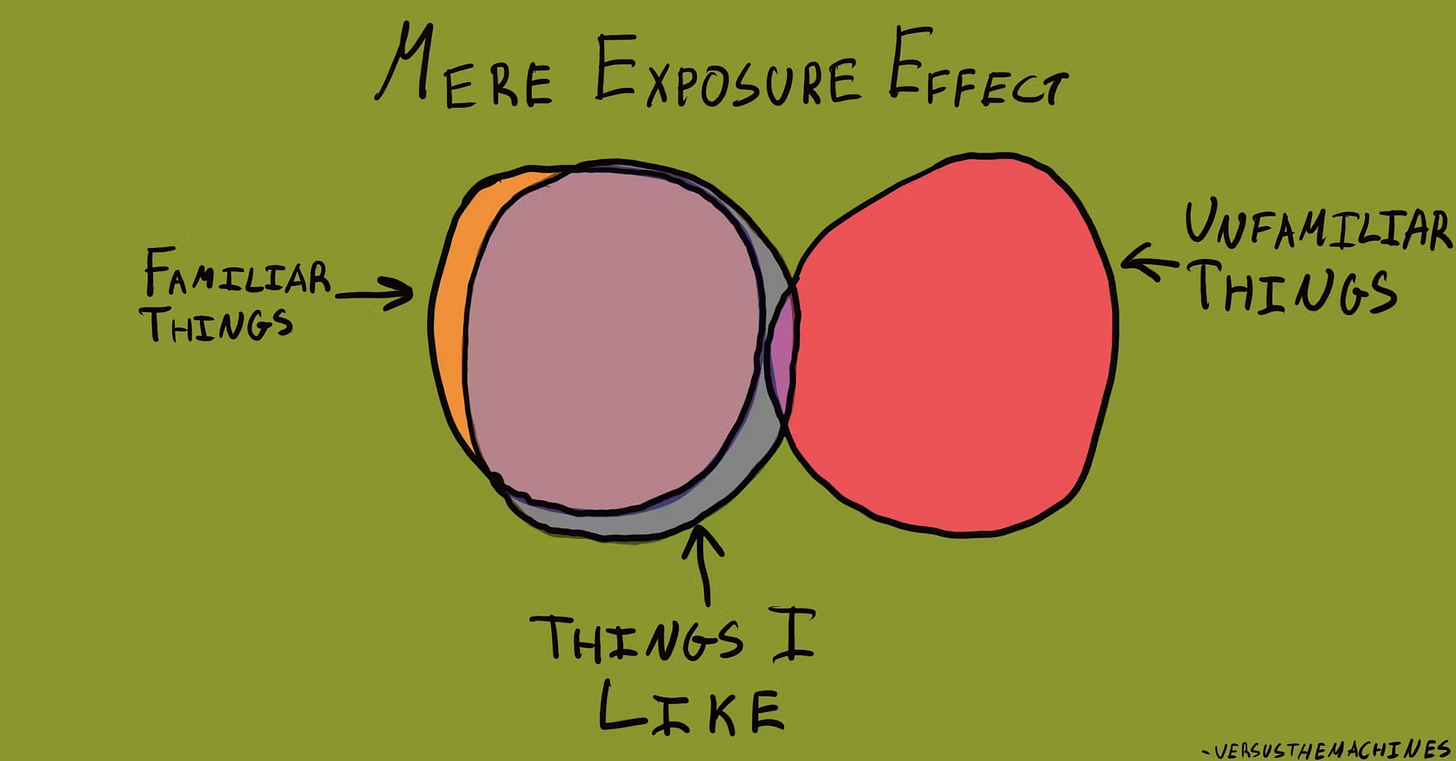

The mere exposure effect is a psychological phenomenon where repeated exposure to something (an object, a person, a song, even a nonsense word) makes us like it more.

It’s one of my favorite psychological phenomena (definitely in my top 3, so much I mentioned it in this series).

The term was first conied by psychologist Robert Zajonc in 1968, and the effect works in a simple way: the more we see or hear something, the more we are inclined to like it.

We feel more positive about it, even if we don’t consciously remember encountering it before.

We prefer things we have been exposed to in the past, and our preference increases as our exposure does.

And the mere exposure effect is everywhere.

It explains why companies bombard us with the same ads, why we gravitate toward familiar faces at a party, and why we start to enjoy a new song after listening to it a few times (also because the radio puts it nonstop).

Why does it happen?

Our brains are wired to associate familiarity with safety. And familiar things signal safety to our brain.

From an evolutionary standpoint, unfamiliar things could be threats.

Thousands of years ago, our survival depended on knowing which plants were safe to eat, which animals were dangerous and those that would make good pets, and which paths were safe to follow.

Trying a different plant, pet or route?

That could get you killed.

On the opposite, familiar things are, by definition, things we’ve survived before. So, when we see something repeatedly, our brains process it more easily - a phenomenon called perceptual fluency.

This ease feels good, and we attribute that good feeling to the thing itself.

How strong is the mere exposure effect? 📈

Very strong.

Zajonc suggests that the relationship between exposure and liking has the shape of a positive, decelerating curve. The more someone is exposed to a stimulus, the more they like it, but the first few exposures are much more powerful than later ones (Zajonc, 1968).

Where does it show up? 🛒👫🎵

The mere exposure effect can be seen everywhere.

For example:

Advertising: Companies repeat ads to make products feel familiar and trustworthy, even if you don’t consciously remember seeing them. And this is why some say that there’s no such thing as bad publicity1. An interesting paper showed that attractiveness ratings of new consumer products increased with exposure frequency (source).

Music: Songs grow on us with repeated listens, up to a point. Several studies on the mere exposure effect have shown that the more people are exposed to unfamiliar music, the more positively they tend to rate it (for example).

Relationships: We’re more likely to become friend, date, or hire people we see often, simply because they become familiar (but sometimes familiarity undermines interpersonal attraction).

Decision-making: When choosing between similar options, we tend to pick the one we’ve encountered before, even if only briefly (another interesting research).

Conclusion

Obviously, the mere exposure effect isn’t universal or unlimited.

If you already dislike something, seeing it more can make you dislike it even more.

However, knowing about the mere exposure effect is a real superpower.

It explains why we get stuck in routines, why we sometimes buy things we don’t need, and why new disruptive ideas can feel uncomfortable at first.

Knowing about the mere exposure effect can also make you get outside your confort zone: if you want to grow, start by noticing what feels uncomfortable simply because it’s new. But give it a few chances.

Because familiarity takes time, and sometimes, so does appreciation.

But remember that familiar doesn’t always mean better.

Sometimes it does, but sometimes it just feels that way.

Here’s what you might have missed recently on Getting Better:

And if you are curious about other science-based insights, read more here.

See you all on Sundays 🗓️

Giacomo

Also because bad is usually stronger than good, as I wrote in this piece.

It makes sense. BTW, have you heard about how Nestlé used this same concept to make coffee popular in Japan, a country filled with tea lovers.

When they first launched their coffee there, it was a massive flop. You are not going to switch from tea to coffee just like that, will you?

So basically they made coffee-flavored chocolate, and it was a massive hit among children, and when they grew up, of course they preferred coffee over tea.

Some people didn't like what Nestlé did, saying they were selling addiction, but I don't know I like to see the glass as half full.

Ah, this must be the reason Taylor Swift became so popular!